Hey! I am an Egyptian computer security researcher and I wanted to share knowledge about binary hacking for you all.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/mahmoudadel0x

Let’s start. I will talk about three topics for now, and in the next session I will continue:

- Computer memory and virtual addressing

- OS functionality and control overview

- Buffer overflows

Computer Memory and Virtual Addressing

Every program gets executed by an already running program and it inherits environment variables from it. This is how the algorithms work. The already running program is the interface for you—it may be the GUI or TTY login shell, etc.

Once a program gets executed by a kernel system call (responsible for this—we will talk about that later), the program moves into the physical RAM and its instructions get executed line by line.

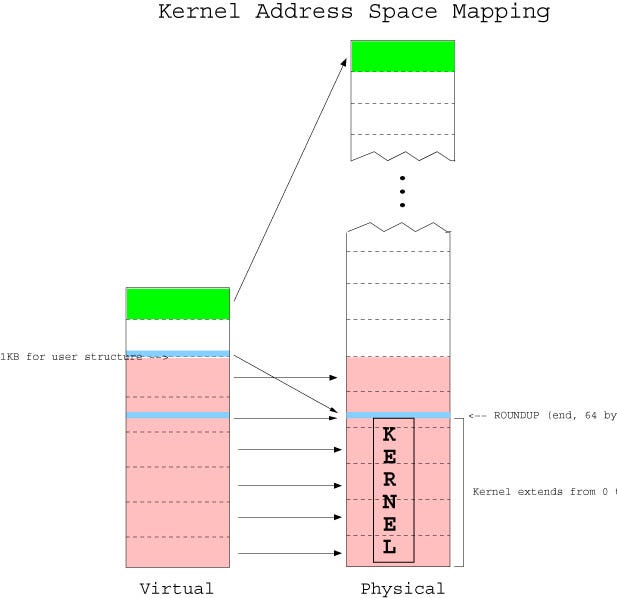

The program can call any function within its segment by its address like 0x774ffffffffff. So how could the kernel manage that access? If any program can access any other program’s segment and steal data! For this, there is virtual addressing. It’s a kernel job to create managed pages containing virtual address space and corresponding physical RAM address space. If the program tries to access out of its page, it gets itself in an interrupt handler.

Image explains the management operation

CPU Modes and OS Functionality, Control Overview

Now let’s talk about how a program actually works in a programmatic way. Example: writing to a file.

When you write to a file in C or PHP or other languages, actually when the code gets compiled/interpreted, it just calls a defined functionality in the OS to do the operation. It is called a system call. You can read about system calls more in Google/Wiki or Linux man pages. That call just gets handled by the kernel—it’s possible in different ways. For example, I will explain an assembly program:

mov eax, 4

mov ebx, 1

mov ecx, dispMsg

mov edx, lenDispMsg

int 80h

The following instructions are adding number 4 in the eax CPU register, which is a system call number that has a corresponding function in the kernel. It is the sys_write call. Move 1 to the ebx register, which is a file descriptor number which is here STDOUT (the terminal virtual device in this situation to show you the message on the screen).

And the length to ecx and the actual message to edx. Now the most important part: int 80h, which is equal to int 0x80. This is a software interrupt (search Google for further info). This interrupt already has a defined section in the kernel interrupt handler table, and so once the CPU executes this, it directs execution to the kernel and the kernel does the rest and takes arguments from CPU registers!

Now to finish the control part: probably you asked, is the application itself able to access that file on the disk? No, because of CPU modes! The kernel is running in a different hardware execution level that allows it to communicate with hardware and BIOS. The kernel has access to the hardware, but the application cannot. So the application in CPU protected mode actually cannot do anything further than what the kernel offers by system calls! Controlling these modes is done by a CPU register called cr0 (search in Google/Wiki for it). This cr0 is a CPU control register. As I said, it gives you control, so you cannot use it from a user application (user space). You can write kernel space code and insert a module into the kernel.

Buffer Overflows

Now you have the basics. Let’s go into the targeted topic: the buffer overflow. What actually happens is using dangerous system calls without bound checking or any limit! Calls like gets(), for example. Not in every situation can you exploit the buffer overflow—no, you cannot always, and you can just cause a denial of service only! In the next session, I will explain the exploitation way. Now let’s understand first.

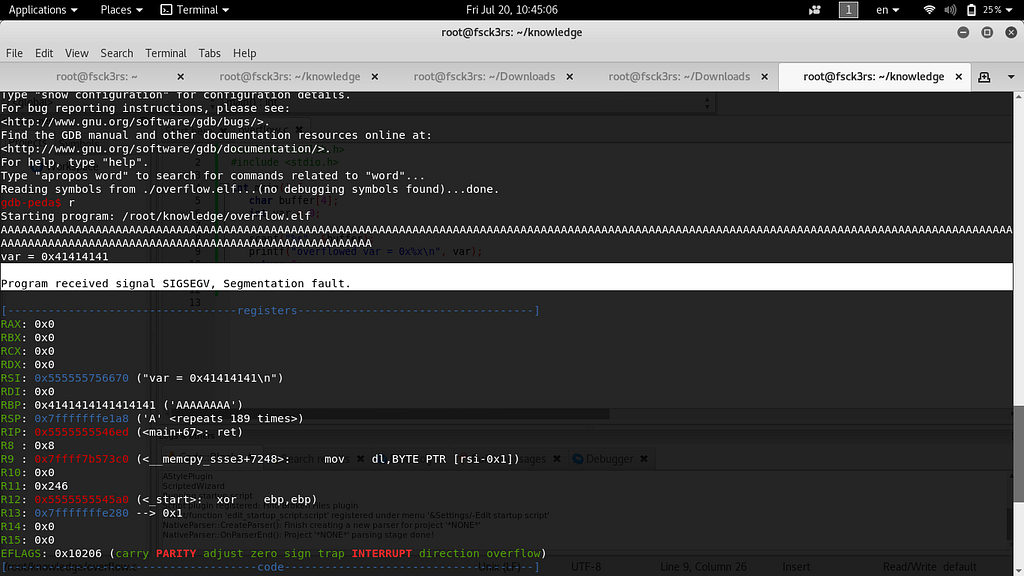

When a program calls a function, it uses call and ret CPU instructions. When call happens, the CPU switches the next instruction to be executed to the first instruction in the called function. After the function is finished, ret gets executed, which means return to the caller. How does the CPU know the caller address? By saving it in the STACK! Example: save eip=0xcaller. When a buffer overflow occurs, the data in the stack segment gets overwritten, so that address gets changed to a new address. Simple C program:

char buffer[4];

int var = 0;

scanf("%s", &buffer);

printf("overflowed var = 0x%x\n", var);

This program declares an array of 4 type characters and a variable named var of type integer and equal to zero, and calls the kernel by scanf system call to take user input with no bound checking. Let’s see the result in the debugger:

Look for segmentation fault and see the stack—we overwritten the stack!

Now this is enough to be able to understand these things. I hope you now understand what happens well. In the next session, I will take you deeper into binary hacking protections and bypasses. Don’t forget to support me by following me on Facebook and Twitter. I am at https://twitter.com/buff3r_overflow, thanks.